(This is the third in a 3-part series where I share some of my “secrets” to scaling a performance marketing business. Here are part 1 and part 2, if you missed them.)

This post is specifically titled “next level” because it assumes the first level of media management is in place. That means having the basics of Customer LTV as well as having a working unit economics model. You can see my posts here and here if you want more info.

The question then moves to, “How would you feel about paying 3x what you currently for customers and being really happy about doing so?” Because it’s likely that you could already be doing so.

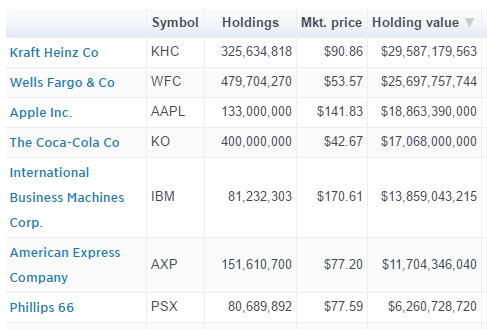

The basis of this possibility comes from the fact that customers from different traffic sources, or from different targeting options, are likely worth different amounts. You may have one ad set on Facebook where the average customer is worth $100 in gross margin and another where the average customer is worth $200. But if you are managing both ad sets based on the same target CPA, then you’re missing out on additional opportunities. If your unit economics model is based on an overall average, then you’re also likely overpaying for the lower-value customers.

This is the key to next-level media management: moving beyond a single target CPA.

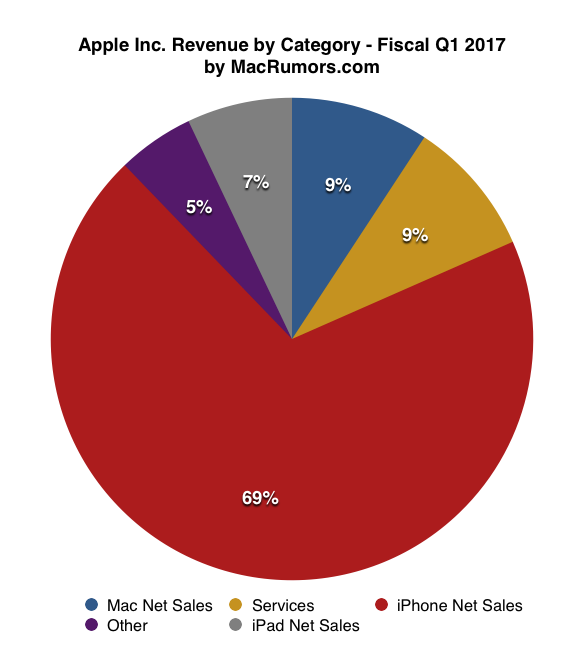

How do you do so? Start segmenting customers into different buckets – that might mean Google vs. Facebook at the outset. Then it might mean different campaigns/audience targeting for Facebook. You might find that creative differences drive different customer values. As a small side note, it’s important to look at the full funnel – so you may have a segment with a really high LTV but also a very low clickthrough rate, which nets out worse than a different segment with an LTV that isn’t the highest. You can’t just look at things in a bubble. A holistic view is important.

But if you net out with a ROAS (Return on Ad Spend) that is significantly different from one segment to another, you may want to consider shifting how you manage these segments. In terms of how you define ROAS (a term I hate; just a bit more than EBITDA…), you can look at day 0 as well as the lifetime gross margin (net revenues less variable expenses) of those customers relative to the cost to acquire them. Day 0 average order value may be a proxy for lifetime, depending on what happens on the back-end. Or you may need to layer on more info. Each business has its own dynamics.

The broader point here is that you likely have customers who are coming from a certain place (station, platform, ad group) that are worth a different amount than another segment. As such, you should be managing how you evaluate those media sources based on different target metrics.

In a best case, your highest-value customers are coming from a channel that you can scale dramatically higher with a new target CPA/ROAS goal. Or you might discover that because of these differences, you should limit the rate to which you’re expanding spend. At a simplistic level, imagine you thought Google and Facebook customers were worth the same when in fact Google customers were worth far less, but you could only scale Google – well, it might take some time to discover that error, and that time and mistake might’ve cost you a lot of money.

Executing on this approach requires solid analytics, which I know is the bane of everyone’s existence. Facebook and GA have different attribution methodologies, so you end up having to triangulate across a couple different approaches. But you’re likely having to do this already. So, making sure you’re sending the right order values back to Facebook and Google, for example, and having a UTM structure that is robust and consistently used across all channels are the foundations to tracking and being able to do the necessary analysis.

Then, it’s a matter of having someone pull the numbers and then managing the media appropriately.

Which leads to one more point. The actual managing of the media.

Meaning, if it’s an agency, then how do you work with them, and vice versa. Or if done internally, how does the internal team operate. I don’t have a rule of thumb on either. I’ve seen agencies work and fail. I’ve seen internal teams work and fail.

In a world where there are a massive number of people running paid traffic, online and offline, it is shockingly difficult to find partners (again, whether internal or external) who can really nail paid traffic. That’s not being rude or disrespectful. If you ask a group of top-notch marketers who they would recommend to run paid traffic, it’s usually a very short list of folks, which the group probably wouldn’t agree on anyways.

That’s because paid media is really hard. Especially when you start scaling. And that’s not simply because of the supposed diminishing returns of scale – I’ve actually seen results improve upon doubling of spend, and at 6-figures plus of weekly media.

Paid media is really hard in part because of a number of factors:

- a) Reporting and tracking – as I already mentioned above, systems disagree. But it takes a rare company that fully understands the differences and gets confident with what they (and you) are really looking at.

- b) The difference is in the details – As spend increases, the number of campaigns, ad sets, stations, and placements increase. At scale, all those little variances, errors, or anomalies that used to be ignored really start to add up. At Beachbody, I’d often say how crazy it was that we had an internal team managing an agency, who had both a client services person and buyer, who then worked with someone at the station. From one perspective, it was absurd to pay someone 6 figures internally when you have these external partners, but when you’re running $100MM of media, just how much do they need to improve to more than ROI their salary and bonus? The answer was enough to justify having them on board.

That’s what happens at scale – minor changes really add up. You can be annoyed, or you can acknowledge the reality and then manage through it (and if you can solve the original annoyance, then great).

- c) Too many people accept the easy answer – I’ve been on so many calls where a hard question was answered with something other than facts. But it sounded really good. For my part, I learned some of this rigor in a Stanford Business School class taught by Andy Grove, founder of Intel. That guy wouldn’t accept a single statement in the class without facts, without data. Answers that sounded nice but didn’t have solid facts to back them up weren’t tolerated. And yet, most businesses operate this way. What sounds like a good explanation only is one when everyone is looking at objective information. Not to say that subjectivity comes into play. As we use to say, “The numbers don’t lie, but they also don’t tell the whole truth.” Clearly, this is a point that transcends media management and into the entire organization, but it’s a particular issue here.

- d) Especially in the digital world, the platforms have a ton of nuance and are constantly changing – TV media management has its particulars and challenges but the number of ways that Facebook has changed, the minor little differences that can happen with targeting differences, and the fact that the people who really understand the platform are likely a handful of engineers who have no exposure to the sales team nor marketers – all these can make TV media management seem like a breeze (it isn’t – I’m just trying to make a point here…). Those changes and subtleties require a close eye and real digging into what’s happening (see a, b and c above).

To be honest, nail this part first (the basics of media management), then get to managing to different CPA’s. Not that it’s an order of magnitude more difficult, but rather it’s necessary no matter what. Very few people are actually doing it well. There’s a skill to managing, be it vendors or employees. None of us is perfect so asking questions and pressing (respectfully) can uncover something that isn’t being optimized.

To summarize, the media part of scaling is about a few things: 1) knowing what a customer’s worth and managing to certain performance metrics; 2) segmenting your customers and traffic to see how and where you should be managing to scale more efficiently, and 3) managing your media partner (agency or internal) tightly.

Everyone wants to reach their “next level.” Hopefully, this 3-part series has helped shed some new insights (or reminders) on what it takes to do so.

(If you have any thoughts on any part of this 3-part series, please leave a comment below.)